Henry, a carpenter in his late 50s who worked for a small business, had been making and refinishing furniture for years. Then he started having difficulty using tools. The quality of his work rapidly declined, and eventually he was fired. At home, his wife grew frustrated with him for forgetting their conversations. He was not doing a good job with chores such as loading and unloading the dishwasher.

Henry went to see a doctor, who referred him for cognitive testing. The results came back “invalid.” Among the potential diagnoses the neuropsychologist came up with was “malingering”—basically faking his cognitive impairment. The specialist apparently did not anticipate that someone so young might have dementia. As a result, Henry’s application for disability benefits was denied.

By the time Henry walked into my clinic at Washington University in St. Louis, he and his family were confused and desperate. His wife thought perhaps Henry was being lazy and didn’t want to work or help around the house. But he seemed to struggle with simple tasks, such as dressing himself, and his problems were getting worse. She was worried.

As a cognitive neurologist, many patients come to see me because they’ve noticed subtle changes in their memory and thinking. Their major question is, “Do my symptoms represent the beginning of a progressive neurological illness like Alzheimer’s disease?” The answer is often not clear at their first visit, even after I take a detailed history, do brain imaging, and check routine blood work. Mild problems with memory and thinking are relatively common and can have many causes, such as poor sleep, stress, sleep apnea, various medical conditions, and certain medications.

When patients with subtle changes in memory and thinking come to our clinic and the cause is unclear, a common strategy has been “cognitive monitoring”—watching patients over time to see if their problems get better, stay the same, or get worse. Some patients improve after interventions such as stopping a medication or starting treatment for sleep apnea. Some patients continue to experience cognitive difficulties but never really worsen. And some patients progressively decline until it becomes clear that they have a neurological disorder. Which leads to another difficult question: Are their symptoms caused by Alzheimer’s disease?

Clinicians define dementia as a decline in memory and thinking that affects a patient’s function in everyday activities. There is a continuum of dementia, from being unnoticeable by people who do not know the patient well to causing complete dependence on others for dressing, bathing, eating, toileting and other simple tasks. Dementia, particularly when very mild, can have many causes, some of which are treatable. Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia in patients older than 65 years. It is characterized by specific brain changes, including the deposition of amyloid plaques. These brain changes slowly worsen over time and can be detected 10 to 20 years before the onset of symptoms.

Not long ago, it was impossible to know for sure whether a patient with cognitive impairment had Alzheimer’s disease or some other cause of dementia without an autopsy. In recent years we have vastly improved our diagnostic capabilities. We can now offer blood tests that can enable earlier and more accurate diagnoses of large numbers of people.

Spinal taps and amyloid PET scans

In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved amyloid PET scans, which can reveal the presence of the amyloid plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease and which are thought to initiate a cascade of brain changes that culminate in dementia. In 2022, the FDA approved the first test for Alzheimer’s disease that measured amyloid proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid or CSF.

For more than a decade, neurologists like me had been using CSF tests to determine whether patients with cognitive impairment were likely to have Alzheimer’s brain changes. While neurologists perform spinal taps to collect CSF to test for a variety of conditions, and it is safe and well-tolerated, most people have never had a spinal tap and it may seem scary. Even if the CSF testing provides a more certain diagnosis, patients often aren’t interested in having a spinal tap unless it has a major impact on their care. Patients will ask, “If I test positive, is there anything you would do differently?” For years, in most cases I have said, “Probably not,” and that I would still treat them with the same medications and follow them in the same way. For this reason, we didn’t do many tests for Alzheimer’s—as my patients put it, “There’s nothing we can do about it anyway.”

There were some exceptions. I did CSF testing on Henry, the carpenter who could no longer build furniture or load the dishwasher. It was positive for Alzheimer’s disease. As I had suspected, Henry had an atypical form of Alzheimer’s that affects brain circuits involved in visual-spatial functioning—exactly the ones Henry needed in his work. With a clear diagnosis, Henry was able to get disability benefits, and his wife understood that his issues were caused by a brain disease.

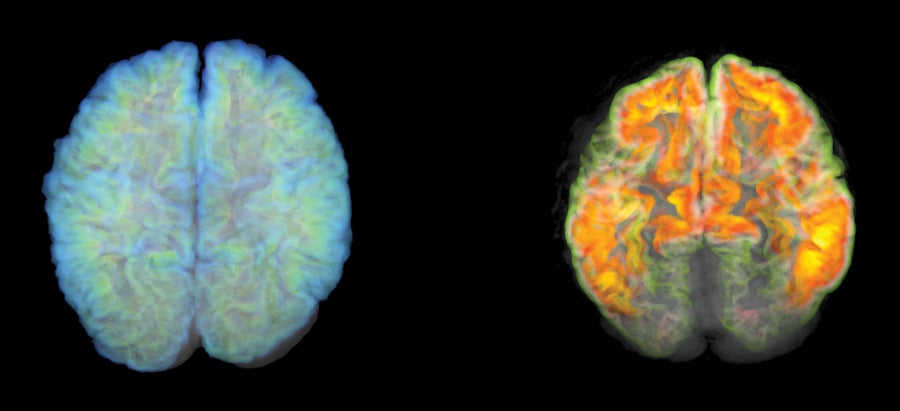

Amyloid PET scans are another technique that can be used to detect and quantify the amyloid plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s. The patient is injected with a very small amount of a radioactive tracer that binds amyloid plaques in the brain. Positron emission tomography (PET) is a sophisticated imaging technique that can take pictures of this radioactivity and visualize the distribution of amyloid plaques in the brain. An amyloid PET scan, however, costs around $6,000 in my medical system. There are also not that many PET scanners. The largest study of amyloid PET, called the IDEAS study, performed 20,000 scans over about 18 months in sites all over the U.S. That’s a lot of scans, but the number of people who might need testing for Alzheimer’s could be in the hundreds of thousands or even millions.

The era of Alzheimer’s treatments

On July 6, 2023, a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease that attacks an underlying cause of disease was fully approved by the FDA. This treatment, lecanemab, works by clearing amyloid plaques from the brain of patients with mild symptoms of Alzheimer’s and slows the progressive cognitive decline. A similar treatment, donanemab, has done well in clinical trials. While we need even better treatments, we are finally starting to make progress against Alzheimer’s. And there are now nearly 150 treatments being studied in clinical trials.

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging can now detect the presence of amyloid plaque in the brain, a sign of Alzheimer's disease. The brain on the right has plaque, while the one on the left does not.

Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute/Science Photo Library

Now that there are specific treatments, testing for Alzheimer’s needs to be done in many more patients, not just the occasional patient like Henry. These treatments are likely to be most effective if given to patients early in the disease, when symptoms are mild. Cognitive monitoring for a year or two isn’t reasonable now that there may be “something we can do about it”. However, relatively few patients with mild cognitive concerns visit a neurologist and undergo a comprehensive dementia evaluation that includes amyloid PET and CSF testing, and many patients are not diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia until the disease has progressed beyond the point that new treatments may be helpful. Now that a treatment is available that is most effective early in the disease, there is a sense of urgency to the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

About three years ago, our memory clinic performed about five spinal taps a month. Now that lecanemab is available, we have scaled up and are now performing about 30 spinal taps per month. It’s difficult to do many more, because the procedure is very time-consuming. We spend about 10 to 15 minutes talking about the procedure and getting consent, which is necessary because most patients have never had a spinal tap and some are anxious about it. The procedure takes about 20 minutes. Afterwards a small number of patients have issues such as back pain or headache, which may require additional follow-up. Amyloid PET scans can be costly, even when insurance covers them, so we haven’t been ordering them very often. Both amyloid PET and CSF tests are highly accurate for detecting the brain changes of Alzheimer’s, but they are too expensive and cumbersome to be used for every person suspected of having Alzheimer’s.

Blood tests for Alzheimer’s

Blood tests are the critical tool needed to enable large-scale testing that may allow for more rapid diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and initiation of treatments when they are most effective. Unlike CSF testing and amyloid PET scans, blood tests are already a routine part of healthcare. When I see a patient with memory and thinking problems, I send them for routine blood work that includes blood counts, blood chemistries, a vitamin B-12 level, and thyroid function studies. However, in patients coming to see me because of cognitive concerns, these routine studies are much less informative than an Alzheimer’s blood test would be.

Since 2017, researchers have made remarkably rapid progress in developing blood tests for Alzheimer’s. Some of these blood tests are now available in the clinic, and many more are on the way. The tests generally measure a handful of different proteins that are strongly associated with Alzheimer’s brain changes. Levels of these proteins can help clinicians decide whether a patient’s cognitive symptoms are likely to be caused by Alzheimer’s. Blood tests are also now being used by clinical trials to identify older, cognitively normal individuals with early Alzheimer’s brain changes who are at high risk of developing dementia.

The first blood test for Alzheimer’s was developed in the laboratory of Randall Bateman at Washington University and became available for clinical use in December 2020. It measured the ratio of two forms of amyloid in the blood and determined a person’s forms of apolipoprotein E, which is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s. More recently, Nicolas Barthelemy, working in Bateman’s laboratory, developed an even better test that measures specific tau proteins in the blood. A version of this tau blood test combined with the amyloid test is now being used in our clinic for select patients. Although studies are still underway and the test is not yet FDA-approved, initial results suggest that this tau blood test has similar or even higher accuracy than CSF tests.

Recognizing that blood tests for Alzheimer’s are critically needed, many other researchers and companies have been working to develop their own. There are now at least 16 Alzheimer’s blood tests in various stages of development. Some tests, like Barthelemy’s, are highly accurate while other tests perform quite poorly. Somewhat surprisingly, the requirements to market a test to patients are low, leading to the availability of Alzheimer’s tests in the clinic that are not well validated and would result in the misdiagnosis of many patients.

How accurate does an Alzheimer’s blood test need to be? Even amyloid PET and CSF tests, while strongly associated with Alzheimer’s brain changes, aren’t perfect. Is it acceptable to misdiagnose one in four patients? (I certainly don’t think so.) Is it acceptable to misdiagnose one in 10 patients, or one in 20? Does it make a difference if the misdiagnosed patient is actually on the borderline of having early Alzheimer’s brain changes?

After returning the results of Alzheimer’s tests to many patients over the past decade, my conclusion is that tests used in clinical diagnosis need to be highly accurate. A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease changes the way patients see themselves and their future; the information guiding this diagnosis must be correct. Accuracy is especially important if patients are going to be started on an Alzheimer’s-disease-specific treatment based on this test result.

After much discussion with colleagues, we generally agree that blood tests used in clinical diagnosis need to be on par with FDA-approved CSF tests or we probably would not use them and ideally would correctly classify 90 to 95 percent of patients. Some of the newest blood tests meet this high threshold, especially because they can categorize individuals as positive, negative, and intermediate. Identifying individuals in this intermediate category, who have borderline levels of Alzheimer’s brain changes, allows much greater confidence in the positive and negative results. Individuals with intermediate results can be re-tested in a year or assessed with another type of test.

Given the greatly increased need for more rapid diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, and the major limitations of spinal taps and amyloid PET, I expect that blood tests will become the dominant approach to testing for Alzheimer’s disease brain changes within a few years. Because blood collection is so accessible, use of Alzheimer’s blood tests would enable us to test most patients presenting for cognitive concerns, rather than the occasional patient like Henry. Broad-based blood testing is the only way that we will be able to identify most individuals with very early symptoms of the disease. Although these Alzheimer’s blood tests are currently used almost exclusively by cognitive neurologists like me, as the tests are better validated and clinicians learn more about them, they will certainly enter into primary care settings. This is largely because there are so many older adults and so few cognitive neurologists.

In another couple of years, there may be another transformation. Clinical trials are now underway to test whether certain treatments, when used in cognitively normal individuals with Alzheimer’s brain changes, can prevent or slow the onset of dementia. If those trials are successful and demonstrate that we can stave off Alzheimer’s dementia, we could enter a time where primary care clinicians screen cognitively normal older individuals at annual visits with blood tests to see whether they have Alzheimer’s brain changes. This may herald an era when Alzheimer’s disease becomes a chronic medical management issue, like high cholesterol, rather than the devastating illness that we know today.

Drop: BlackJack3D/iStock; Eye: DraganaB/iStock; Chromosome: Jian Fan/iStock; Phone: NatalyaBurova/iStock

This article is part of The New Age of Alzheimer’s, a special report on the advances fueling hope for ending this devastating disease.