Though relatively unknown at the time, one participant in the 1893 World’s Fair later became a famous fixture of food advertising and a part of many people’s kitchens for more than a century. For the past ninety-seven years, the final resting place of the real woman behind the character was an unmarked plot of grass in a cemetery on Chicago’s South Side.

A sign welcoming guests to the September 5, 2020, headstone ceremony for Nancy Green.

On Saturday, September 5, 2020, cultural historians, civic leaders, and interested members of the community gathered at Oak Woods Cemetery for a ceremony celebrating the life and contributions of Nancy Green (1834–1923). Organizer Sherry Williams, founder and president of the Bronzeville Historical Society, unveiled a new headstone to commemorate the Black woman who first portrayed “Aunt Jemima” while preparing thousands of pancakes at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The headstone was the culmination of more than a decade of research and a successful fundraising effort this spring by Williams. The ceremony came just months after Quaker Oats announced that it would retire their Aunt Jemima food brand. The story of how a former slave became one of the first Black corporate models in the United States runs through a display booth at the 1893 World’s Fair.

A new headstone for Nancy Green, the original “Aunt Jemima,” in Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

Aunt Jemima pancake mix

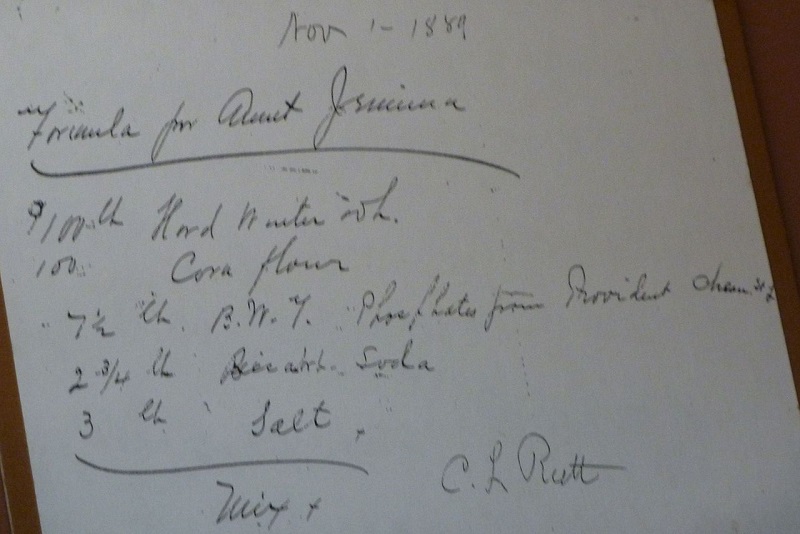

The story begins a few years before the Columbian Exposition in St. Joseph, Missouri, where Chris L. Rutt, a local newspaper editor, and Charles G. Underwood purchased a flour mill in 1888. A glutted market prompted the entrepreneurs to invent a new flour product in the summer of 1889. By preparing a mixture of wheat flour, corn flour, lime phosphate, and salt, they created America’s first ready-made pancake mix.

Chris Rutt’s original recipe for Aunt Jemima pancake mix, dated November 1, 1889, is held in the Patee House Museum in St. Joseph, Missouri. [Image from Wikipedia.]

When Rutt and Underwood went bankrupt in 1890, they sold the company and their pancake mix formula to the R. T. Davis Mill Company. Owner R. T. Davis injected needed capital, built a wider distribution system, and launched the next stage of the Aunt Jemima legacy.

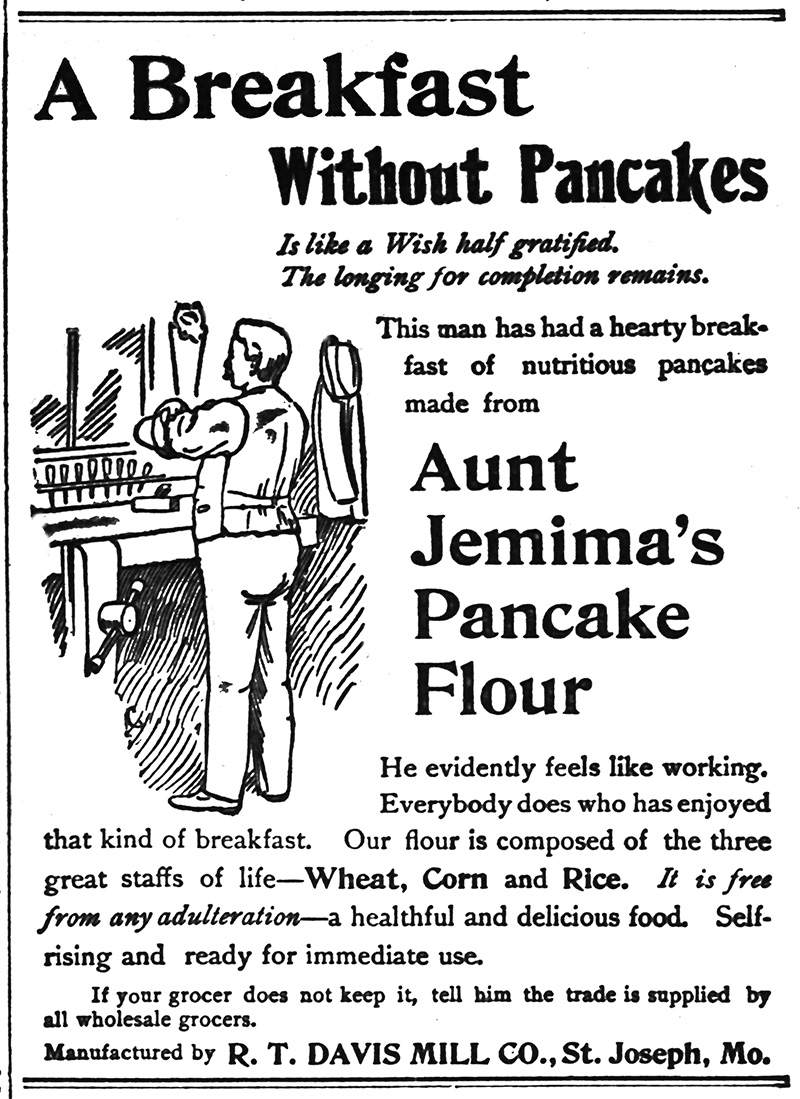

An 1890 advertisement listing the new Aunt Jemima pancake mix. [Image from the St. Joseph Gazette Herald Feb. 16, 1890.]

An 1893 advertisement for Aunt Jemima’s pancake flour [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Jan. 2, 1893.]

Nancy Green becomes Aunt Jemima

By the spring of 1890, news about the upcoming World’s Fair in Chicago had reached St. Joseph, and excitement grew in the following years. While planning his company’s exhibit at the Fair, Davis decided to create an Aunt Jemima living persona who would prepare pancakes on site for visitors from around the world. For his “living trademark,” Davis found Nancy Green.

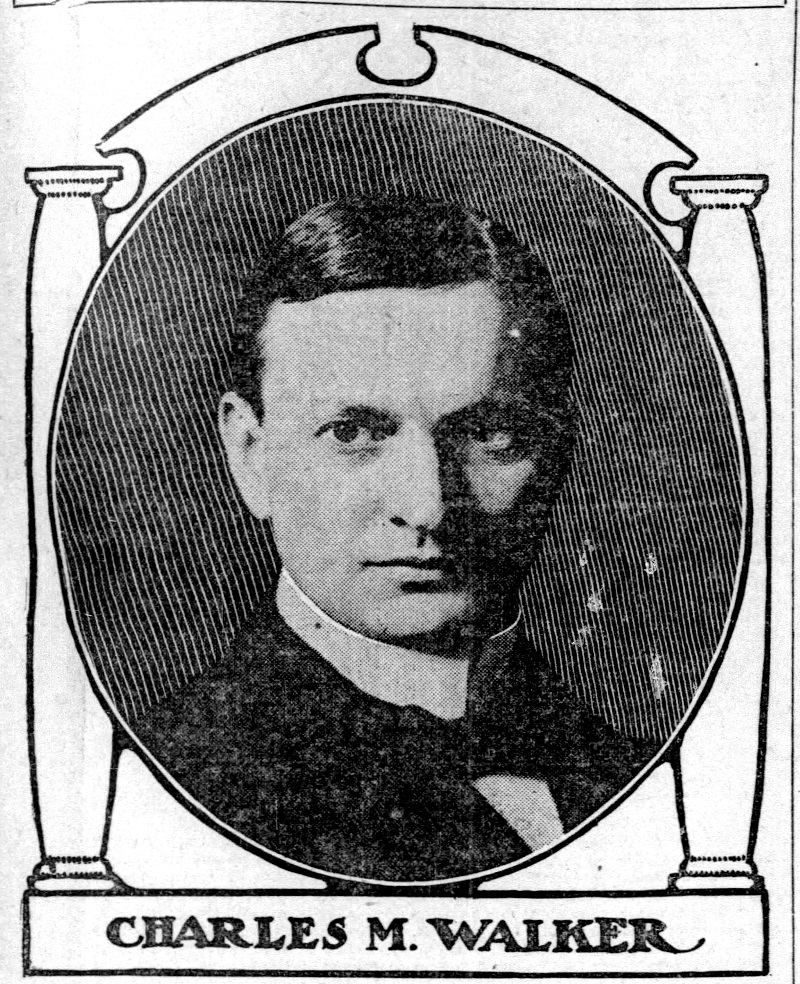

Green was a former slave working as a domestic in Chicago. Born on March 4, 1834, in Mt. Sterling, Kentucky, Green obtained her freedom sometime during her late teens and began working as a nanny and housekeeper to the Walker family in Covington. Samuel J. Walker, son of Kentucky governor Charles S. Morehead, moved his family to Chicago in 1872, just after the great Chicago fire. Walker bought up property on Ashland Avenue from Madison Street to 39th Street, part of which developed into a neighborhood for former Kentuckians, including future mayor, Carter Harrison, Sr. Growing up under the care of Nancy Green as their nurse were two children of Samuel J. Walker who became well-known Chicago citizens: Judge Charles Morehead Walker (Sept. 23, 1859 – May 13, 1920) and Dr. Samuel J. Walker, Jr. (Nov. 19, 1867 – Aug. 19, 1924).

One of the boys under the care of Nancy Green was Judge Charles Morehead Walker of Chicago, shown at age 41 in this 1901 photograph. [Image from the Chicago Tribune, Aug. 4, 1901.]

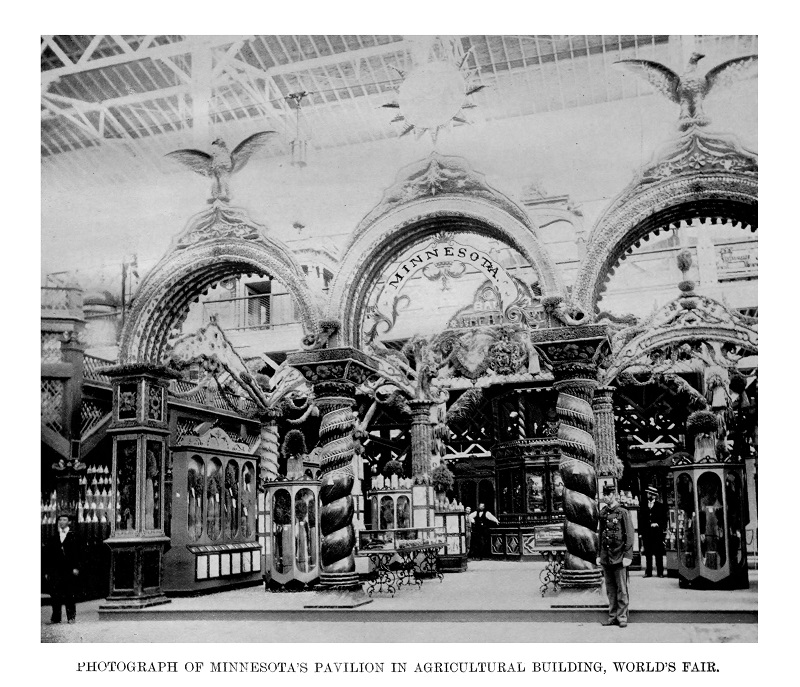

Exhibiting in the Agricultural Building

At the World’s Columbian Exposition, exhibits of flour and mill products filled one stretch of the east balcony of the Agricultural Building. Creative displays included a castle built out of flour bags, a reproduction of a 150-year old mill, and a large flour barrel display made from 10,500 little barrels. The R. T. Davis Mill Company display featured two notable attractions, Aunt Jemima and the “world’s largest flour barrel.”

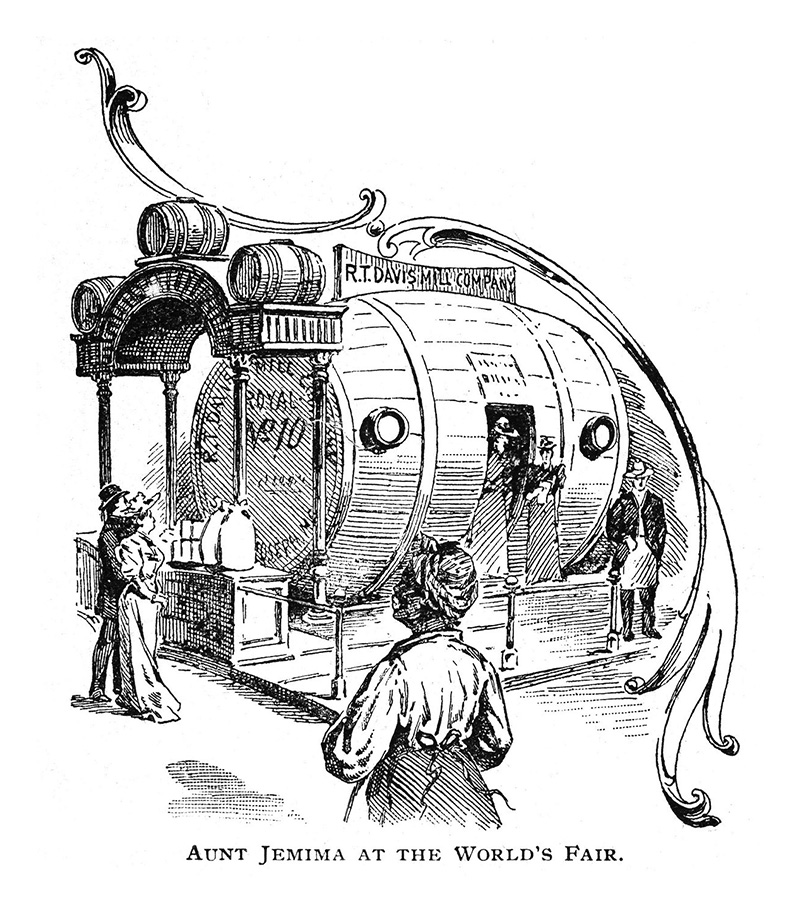

An advertisement for the R.T. Davis Mill Company showing “The World’s Largest Flour Barrel” display at the 1893 World’s Fair, from the Aug. 14, 1893 issue of the Kansas City Star.

The mammoth barrel—described by the company at the time as being sixteen feet long, twelve feet in diameter at the center, and ten-and-a-half feet at each end—laid on its side to form a small cabin.[“R. T. Davis Mill Co.”] (Other sources report the barrel as either about eighteen [“Quaint and Curious”] or twenty-four feet long.[Wright]) The heads of the barrel were made of plate glass (reportedly the largest single pieces of plate glass at the World’s Fair) with company’s trademark flour brand logo displayed in sixteen-inch gold-leaf lettering outlined with blue and black. The glass heads were backed with a sample of the company’s Royal No. 10 flour, making for an impressive advertising sign. A canopy, sixteen-feet tall and six-feet wide, extended out from each end of the huge barrel. Six smaller flour barrels and a sign with the company name topped the structure.

In the center of the barrel were openings on each side with steps leading to an interior reception room where R. T. Davis Mill representatives greeted potential customers. Visitors could sign a guest registry or browse a selection of current St. Joseph newspapers. Above the front doorway was mounted a placard that read: “Walk through the largest barrel in the world and get an Aunt Jemima pancake on the other side.”

On the other side of the barrel, an “exceedingly fine and tasty booth” was constructed from neatly arranged boxes of Aunt Jemima pancake mix. Old Aunt Jemima, portrayed by Nancy Green, greeted visitors and served them hot and fresh pancakes. She busied herself making and dishing up samples and all the while repeating: “Aunt Jemima pancake flour—wheat, corn and rice—the best in the world.” [“The Editor’s Vacation”]

If the flour barrel was the largest in the world, at least some of the pancakes may have been the smallest. However slight, the miniature flapjacks impressed at least one newspaper reporter:

“I walked through, interviewed Aunt Jemima and got a pancake. It almost brought a tear to my eye. I could not think of eating the delicate, beautiful thing. I had a silver dollar in my pocket, by chance. I placed it gently on the pancake and just enough of the yellow fringe showed around the border to make a fair model of the annular eclipse of the sun. The weight of the pancake was not quite one-fifth that of the dollar. But it was ‘free.’” [Beadle] Whenever visitors from St. Joseph arrived at the booth, Green shook their hands and “gave them a double serving of the toothsome pancakes, hot off the griddle.” [“Aunt Jemima is Dead”]

This illustration of Aunt Jemima’s pancake booth depicts some rather small pancakes. [Image from the Harrisburg (PA) Telegraph Aug. 16, 1893.]

The Wizard of Menlo Park meets Aunt Jemima

Working their way through the Agricultural Building, visitors could sample so many different foods and drinks that many reportedly made a meal out of following the “free lunch route.” A visitor from Minnesota reported trying “lemon jelly, pickles, mustards, catsups, butter, oatmeal, Quaker oats, root beer and Aunt Jemima’s pancakes.” [Day] Many displays touted diets meant to improve health and live a long life. A reporter from the Chicago Inter Ocean observed that visitors curious about how to become a centenarian can “visit the Agricultural building and learn how it may be done by the use of Aunt Jemima’s pancakes or German mineral water, by root beer or a new-fangled coffee pot, by cocoa or sour milk—all without money or price.”[“Blessed the Giver”]

One such visitor to Aunt Jemima’s stand was none other than Thomas A. Edison, who attended the Columbian Exposition for a few days in August. Thinking he was lost on the fairgrounds one afternoon (see “Quietly Enjoying His Lunch“), his companions eventually found him in the Agricultural Building enjoying a pancake. Columbian Exposition historian Hubert Bancroft summarized the incident this way: “Among the jokes that passed current as to distinguished visitors was one concerning Edison, the great electrician, who, it is said, being lost for hours to his friends during a visit to the Fair, was finally discovered in one of these galleries eagerly devouring a large pancake spread with jelly.” [Bancroft, 396]

The St. Joseph Gazette Herald shared the story with hometown pride, reporting that Mr. Edison was spied at last at the R. T. Davis Mill company’s exhibit “with an Aunt Jemima pancake in each hand, thoroughly enjoying himself.” [“Edison Was Enjoying Himself”] The number of then-famous or to-be-famous people who crossed paths on the 1893 fairgrounds—often unbeknownst to each other—is fascinating to consider.

For their Aunt Jemima Pancake flour, soft winter wheat flour, and hard winter wheat flour, the R. T. Davis Mill Co. of St. Joseph received a medal and diploma from the Columbian Exposition Committee on Awards. Behind the scenes was another winner. The company proclaimed Nancy Green the “Pancake Queen” and signed her to a lifetime contract to represent Aunt Jemima. She performed in the role at the other expositions for decades.

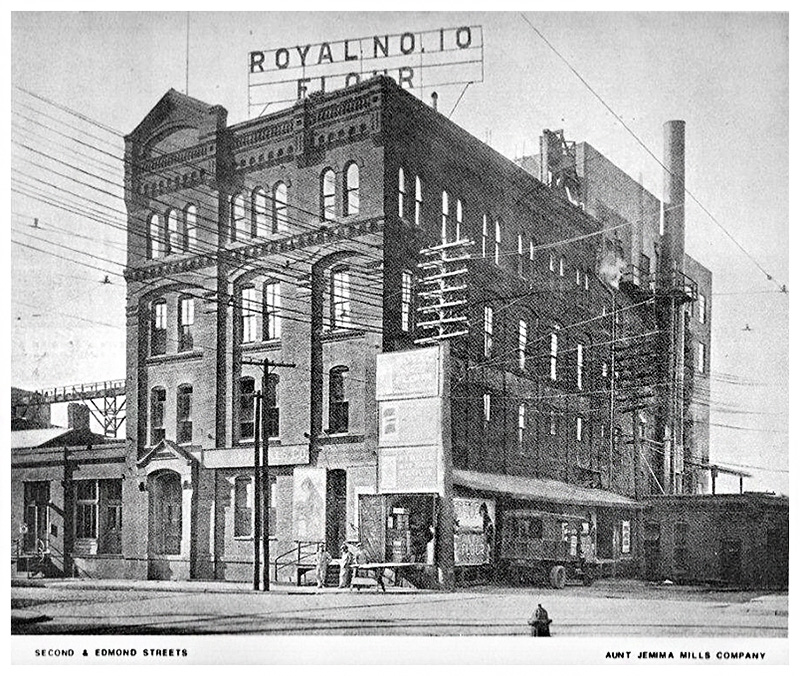

The Aunt Jemima Mills Company in St. Joseph, Missouri.

The Life of Aunt Jemima

While fame did not come to Nancy Green in 1893 or in her lifetime, her character of Aunt Jemima became a familiar face in many American homes. After the Chicago fair, the R. T. Davis Mill Company amplified Aunt Jemima’s real fame by creating a fictional one, thereby launching the next stage in the evolution of their living trademark.

“Aunt Jemima at the World’s Fair” as depicted in The Life History of Aunt Jemima (1895).

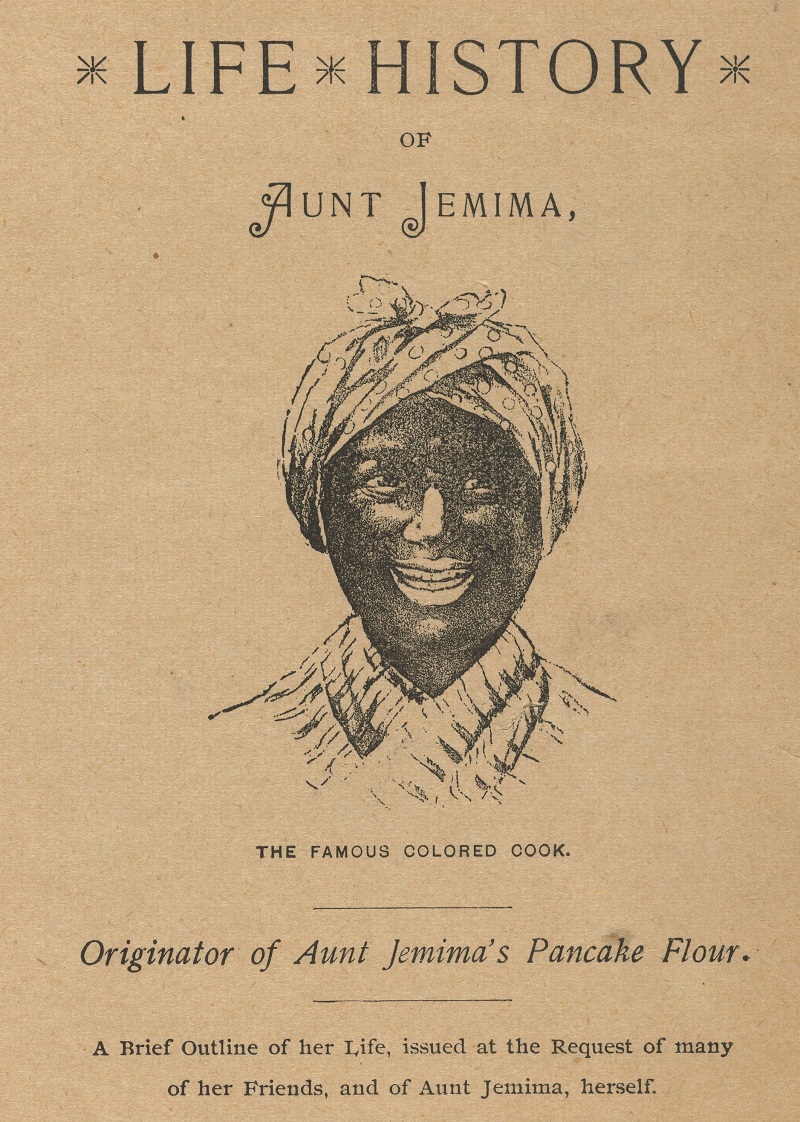

The fabricated backstory of Aunt Jemima and her “famous” southern pancakes came from the imagination of Purd Wright, who wrote advertising copy for the R. T. Davis Milling Company. Wright, who claimed to have tasted their first perfected pancake, originated the company’s famous advertising slogan, “I’se in town, honey.” After the 1893 World’s Fair, he wrote a fictional biography of the company’s star salesperson, published around 1895 as an illustrated pamphlet titled Life History of Aunt Jemima, the Famous Colored Cook. Originator of Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Flour. A Brief Outline of her Life, issued at the Request of many of her Friends, and of Aunt Jemima, herself.

His fictional narrative places Aunt Jemima in a log cabin on the Old Higbee Plantation along the banks of the Mississippi River in Louisiana. Born into slavery there, she became the cook for Colonel Higbee and used her “surprising knowledge of the properties and possibilities of their wholesome ingredients” to combine wheat, corn, and rice grains into pancakes. The pamphlet even offers “a truthful representation” of Aunt Jemima feeding prominent leaders of the Confederacy. Years after the Civil War, a representative of the R. T. Davis Mill Co. was among a group who rediscovered the “celebrated” cook still living in the cabin in 1886. The company—so the story goes—then purchased the recipe from Aunt Jemima, paying her in gold, and made her an employee. The pamphlet closes with this description of their World’s Fair exhibit:

“… commanding the wonder and admiration of all visitors to agricultural hall, was the most remarkable and successful exhibition in the food product. This display was neither more nor less than the original Aunt Jemima, herself, making pancakes from Aunt Jemima Flour, each package of which bears her portrait. It can be imagined that it did not take the visitors to the World’s Fair, especially those from the South, long to learn of this attraction. The consequence was that at times the crowd was so great around this exhibit that the assistance of special police had to be secured to keep it moving, as it often blockaded seriously that portion of the building. Over 50,000 orders were received at the booth alone for packages of Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Flour. These orders came from Europe, Canada, and all parts of the United States. The World’s Fair Committee on awards did not hesitate to bestow the highest medal and diploma on the Aunt Jemima Pancake Flour and the celebrated Royal No. 10 Flour.”[Wright]

Title page from the fictional biography Life History of Aunt Jemima (1895). [Image from Harvard University.]

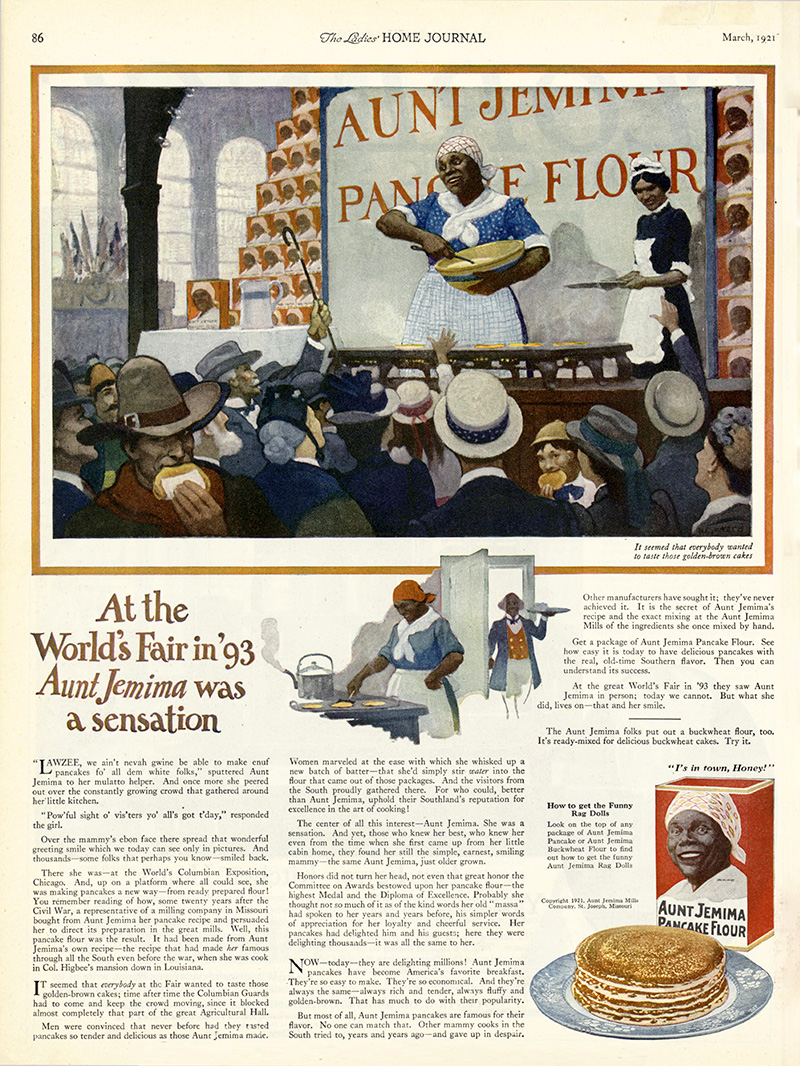

“At the World’s Fair in ’93 Aunt Jemima was a sensation” advertisement in the March 1921 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal.

Almost three decades after the Fair, the blurring of fact and fiction continued with a nostalgic advertisement. The J. Walter Thompson Advertising Agency commissioned renowned artist N. C. Wyeth to create a depiction of the Aunt Jemima exhibit at the Columbian Exposition. Wyeth’s oil painting, today in the collection of the Brandywine River Museum of Art, illustrated an Aunt Jemima Mills Company advertisement appearing in the February 12, 1921, issue of the Saturday Evening Post and the March 1921 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal.

The advertisement “At the World’s Fair in ’93 Aunt Jemima was a sensation” extended some old myths and may have created new ones. The text repeated the fictional story from the 1895 pamphlet that the R. T. Davis Mill Company had bought from Aunt Jemima her pancake recipe, which had “made her famous through all the South even before the war.” The display at the 1893 World’s Fair was so popular (stated the advertisement) that “time after time the Columbian Guards had to come and keep the crowd moving, since it blocked almost completely that part of Agricultural Hall.” This routine work performed by the Columbian Guard in each of the great exhibition halls has evolved into modern claims that the Aunt Jemima required police and security to maintain order. Finally, the copy ironically observes that “those who knew her best, who knew her even from the time when she first came up from little cabin home, they found her still the simple, earnest, smiling mammy—the same Aunt Jemima, just older grown.”

A Columbian Guard with no crowd to control in front of the Minnesota Pavilion inside the Agricultural Building at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume I. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

Aunt Jemima after Nancy Green

According to newspaper reports, Nancy Green died on August 30, 1923, from injuries suffered when she was hit by an automobile just around the corner from her home at 4543 S. Indiana Avenue in Chicago. While standing on the sidewalk underneath the elevated train track at E. 46th Street, the eighty-nine-year old was struck by an automobile after it collided with a laundry truck. A grand jury found the two drivers criminally responsible for manslaughter; one of whom was a neighbor. Green had been an active member of the Olivet Baptist Church, where her funeral was held on September 1, 1923. Interment in Oak Woods Cemetery was in an unmarked grave. Nearby rests other Black luminaries, including civil rights activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Chicago Mayor Harold Washington, and Olympic track and field champion Jesse Owens.

The former home of Nancy Green at 4543 S. Indiana Avenue in Chicago.

Even during Nancy Green’s run as Aunt Jemima at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, at least one other woman performed as the corporate icon. A parade held in St. Joseph, Missouri, on July 26, 1893, celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the city’s founding. A float sponsored by the R.T Davis Milling Company featured an Aunt Jemima “seated on her throne high above a host of willing subjects who acknowledged allegiance to her.”

After Green’s death, many other women stepped into the role of Aunt Jemima, and in January 1926, Chicago-based Quaker Oats purchased the struggling Aunt Jemima Mills Company. Over the years, the image of Aunt Jemima used in marketing and advertising has changed, with the last make-over—adding pearl earrings and a lace collar—in 1989. In 2020, Quaker Oats (now a subsidiary of PepsiCo) announced that their Aunt Jemima pancake and syrup brand would come to an end.

“We recognize Aunt Jemima’s origins are based on a racial stereotype,” Quaker Foods vice president and chief marketing officer Kristin Kroepfl said in a statement. “While work has been done over the years to update the brand in a manner intended to be appropriate and respectful, we realize those changes are not enough.” The company announced that it plans to donate at least $5 million over the next five years to support the African American community.

The complex history of the Aunt Jemima character has sparked a wide range of commentary among scholars of Black cultural history and popular culture. (See, for example, Maurice M. Manring’s Slave in A Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima and Kimberly Wallace-Sanders’ Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory.) In his study of the Black presence at White City, Christopher Robert Reed offers this perspective on Nancy Green’s role: “Hers was not just to be an affirmation of a negative racial stereotype; hers was a promise to housewives of liberation in their kitchens, offering them more free time and admission into the modern world.” [Reed, 102]

At the World’s Fair in 1893, Aunt Jemima was a sensation. As her image fades from grocery store shelves, it may be more important than ever to preserve the legacy of Nancy Green and her unique contribution to the World’s Columbian Exposition. The new headstone for her grave in Oak Woods Cemetery is valuable commemorative marker.

SOURCES

“2 Drivers Held for Killing of ‘Aunt Jemima’” Chicago Tribune Sept. 8, 1923, p. 8.

“At the World’s Fair in ’93 Aunt Jemima was a sensation” Ladies’ Home Journal March 1921, p. 86.

“Aunt Jemima is Dead” St. Joseph (MO) News-Press Sept. 5, 1923, p. 3.

“Aunt Jemima, of Pancake Fame, is Killed by Auto” La Crosse (WI) Tribune, Sept. 6, 1923, p. 8.

“‘Aunt Jemima’ of Pancake Fame is Killed by Auto” Chicago Tribune, Sept. 4, 1923, p. 13.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.

Beadle, J. H. “Chicago Is Level” Newark (OH) Advocate Aug. 12, p. 12. This syndicated newspaper story ran in newspapers across the country.

“Blessed the Giver” Chicago Inter Ocean Aug. 16, 1893, p. 19.

Brownlee, Richard S. “Editor Was Inventor of Aunt Jemima Pancakes” Missouri Historical Review 66, 1, October 1971, p. 92.

“Charles Morehead Walker” Chicago Tribune Aug. 4, 1901, p. 43.

Davis, Elizabeth “Historically Yours: ‘Aunt Jemima’ born in St. Joseph” St. Joseph (MO) News Tribune, June 4, 2019.

Day, Mary Pearl “Our Girl” Freeborn County Standard (Albert Lea, MN) Aug. 30, 1893, p. 1.

Doneghy, Sarah “Aunt Jemima: It was Never About the Pancakes” Black Excellence Jan. 30, 2018 https://blackexcellence.com/aunt-jemima-never-pancakes/

“Edison Was Enjoying Himself” St. Joseph Gazette Herald Sept. 17, 1893, p. 3.

“The Editor’s Vacation” Iron County (MO) Register, Sept. 14, 1893, p. 1.

Fauzia, Miriam “Fact check: Aunt Jemima model Nancy Green didn’t create the brand” USA Today, Jun. 30, 2020.

“Glorious” St. Joseph Gazette-Herald July 27, 1893, p. 2.

Manring, Maurice M. Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima. University of Virginia Press, 1998.

McElya, Micki; Clinging to Mammy : The Faithful Slave in Twentieth-Century America. Harvard University Press, 2009.

“Nancy Green, the original ‘Aunt Jemima’” African American Registry https://aaregistry.org/story/nancy-green-the-original-aunt-jemima/

Palace, Steve “Say Goodbye to Aunt Jemima – Breakfast Icon to be Rebranded” The Vintage News Jun. 18, 2020 https://www.thevintagenews.com/2020/06/18/aunt-jemima/

“Quaint and Curious” Wilmington (DE) Daily Republican Sept. 26, 1893, p. 3.

“R. T. Davis Mill Co.” St. Joseph (MO) Herald July 26, 1893, p. 31.

Reed, Christopher Robert “All the World Is Here!” The Black Presence at White City. Indiana University Press, 2000.

Turley, Alicestyne “The real story behind ‘Aunt Jemima,’ and a woman born enslaved in Mt. Sterling, Kentucky” Lexington Herald Leader, June 25, 2020.

Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. University of Michigan Press, 2009.

“World’s Columbian Exposition. List of awards, as copied for Mrs. Virginia C. Meredith, Chairman, Committee on Awards, Board of Lady Managers, from the official records in the office Hon. John Boyd Thacher, Chairman, Executive Committee on Awards.” http://chsmedia.org/media/fa/fa/LIB/WCE_AwardsList_Domestic.htm

[Wright, Purd] Life History of Aunt Jemima, the Famous Colored Cook. Originator of Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Flour. A Brief Outline of her Life, issued at the Request of many of her Friends, and of Aunt Jemima, herself. J. Ottman Lith. Co. [1895?]

Leave A Comment