The Rise of Older Mothers

Everyone is having fewer babies in the U.S.—except women in their 40s.

Women in the United States are having children at record low rates, according to the latest statistical release from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2017, births were down 2 percent from 2016 and were at their lowest in 30 years. In fact, the only American women who are consistently having more babies than before are those over 40.

Births among Hispanic and white women declined slightly, according to the CDC, but among black women, they remained steady.

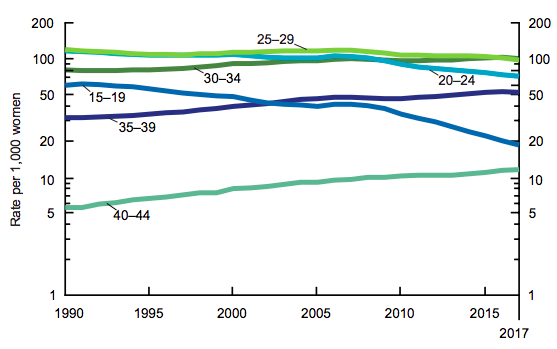

Fertility has generally been declining among women in their 20s and rising among women in their 30s and 40s for several years. The fertility rate was around replacement level—the rate at which a generation can replicate itself—until 2008, and it’s been declining since.

One factor behind the decline might be declines or delays in marriage: Births to never-married women are down more than births to women who have been married, as Lyman Stone points out at the Institute for Family Studies.

Birth Rates by the Age of the Mother

The rise of screen time might be another factor that has caused Americans to have less sex, said W. Bradford Wilcox, a sociologist at the University of Virginia, at a recent roundtable discussion for reporters at the American Enterprise Institute, the free-market think tank in Washington. Think of a couple, he said, “and it’s Wednesday night, and they start Netflix going, and they keep watching Netflix and they don’t do ... anything else.”

Birth rates also declined last year for women under 40 but rose for women older than 40, likely in part thanks to improved fertility technologies like in-vitro fertilization. This suggests, as a Pew Survey found earlier this year, that more women are delaying childbirth into their late 30s and early 40s, but ultimately choosing to have children in the end—just perhaps not as many. Women seem now more likely than before to get their degrees, work in the labor force, then have a baby as a sort of capstone to a life of education and labor. It’s too soon to say whether this delayed childbearing will result in fewer babies overall.

Fertility is declining in many developed countries, and whether that’s a problem depends on how you look at it. Since the recession hit, the United States has spent $40 billion less on births, according to Wilcox—a savings that helps preserve Medicaid and food-stamp funds. However, he added, “in the long term, it might present long-term challenges to the funding of things like Social Security and Medicare.”

Although Hispanic women’s fertility has declined the most in recent years, proportionately to their population, foreign-born immigrant women are still more likely than American-born women to have children. That means more generous immigration quotas might help avert an American baby bust. “Immigration matters a lot to fertility in the United States, because immigrant moms account for a disproportionate share of births in the United States,” said Gretchen Livingston, of the Pew Research Center, at the AEI event.

Still, as Stone noted in The New York Times recently, “the gap between the number of children that women say they want to have (2.7) and the number of children they will probably actually have (1.8) has risen to the highest level in 40 years.” That means women aren’t having quite as many children as they’d like—potentially because women who have children between the ages of 25 and 35 suffer a wage penalty they never recover from. That could be something these 40-something moms are trying to avoid.

On the plus side, the CDC report notes teen birth rates were also down by 7 percent from 2016—continuing their steady decline since 2007. Experts in teen pregnancy credit the drop in teen births to the rise of long-acting, reversible contraceptives, or LARCs, which have been made available through the Title X program and the expansion of health insurance through the Affordable Care Act. However, some women’s-rights groups fear this particular trend won’t last, given some recent efforts by the Trump administration.

Last year, the uninsured rate rose in 17 states for the first time since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act because of increasing rates on ACA insurance plans that are, at least in part, considered to be the result of uncertainty in the marketplaces introduced by the Trump administration.

Meanwhile, Planned Parenthood, the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association, and American Civil Liberties Union are currently suing the Trump administration over what they see as changes to the Title X program that would emphasize the rhythm method and abstinence over contraception.