The new coronavirus pandemic erupted in the midst of the 2020 U.S. census, creating a new set of challenges to achieving an accurate count. The Census Bureau has since delayed field operations, suspended in-person outreach events and asked Congress for an extension of legal deadlines to deliver data. The COVID-19 pandemic also sent many Americans on the move to places other than their usual residence – and they may not know where or how they should be counted.

Americans who relocated because of the coronavirus outbreak include millions of college students sent away from their dorms (or from study abroad), young adults working remotely who returned to their parents’ homes and people who fled urban areas for rural communities. The census is based on the idea that most people in the United States have a “usual residence,” and that is where they should be counted. But what does that mean for people who unexpectedly relocated due to the pandemic?

Census Bureau rules state that most people should be counted at their usual residence on Census Day, which is April 1. The census concept of “usual residence” is not based on where you vote or pay taxes or otherwise are a legal resident. It is defined as the place where you live and sleep most of the time. This idea goes back to the law that governed the nation’s first census, in 1790, which stated that people should be counted at their “usual place of abode.”

The rules for determining where people should be counted are complicated. They lay out how to determine a usual residence or where people should be counted if they don’t have one. But these rules are not always intuitive, and many people live in ambiguous situations that may not be covered by clear rules about where they should be counted.

Where someone is counted is important, because census numbers affect how political representation and federal funding are divided up among states and localities. That’s one reason why the Census Bureau motto is to count everyone living in the U.S. once, only once and in the right place.

Simple answer for college students but not others

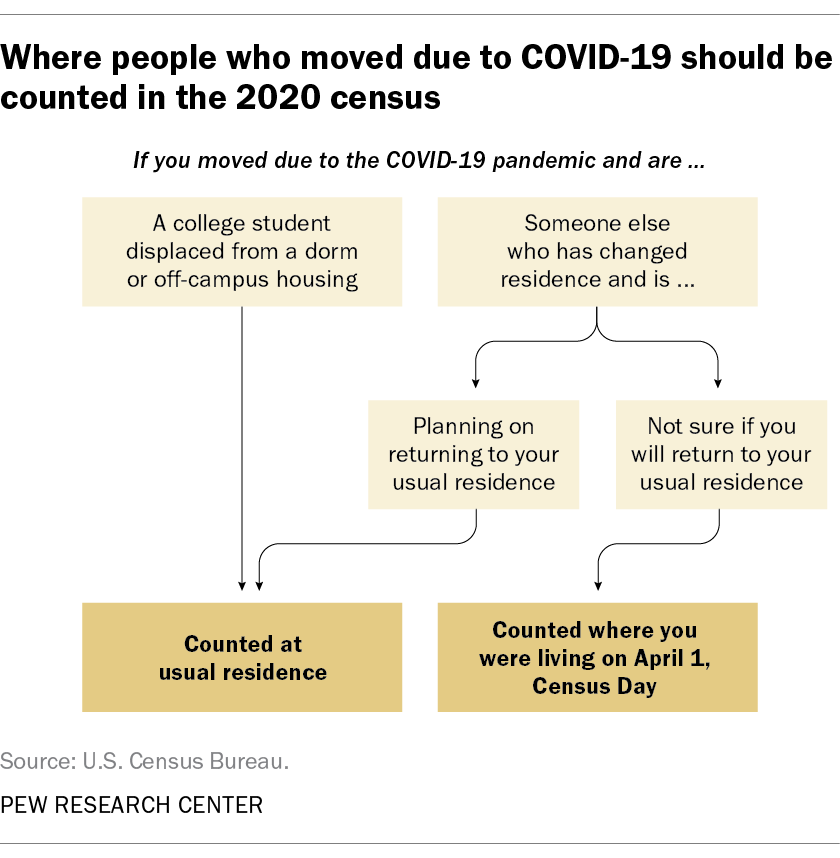

One group for whom there is a simple answer to where they should be counted is college students sent away from their dorms or off-campus residences. In ordinary times, they are counted at their college housing during the school year. Even if they are living elsewhere now due to COVID-19, they should be counted at their college housing, because that is where they normally would be, according to recently provided Census Bureau guidance about college students whose whereabouts were affected by the outbreak. Otherwise, the federal funding that would go to those college towns based on the student numbers could be reduced.

But for others, especially those who are not sure where they will be living in the future, the answer may not be as clear-cut.

Census Bureau rules state that people who are temporarily living elsewhere but intend to return to their usual residence should be counted at their usual residence. Those who are not sure whether they will return to their usual residence after the pandemic crisis ends should be counted at the address where they are living on Census Day.

The idea of being counted in the place where you intend to return is similar for people who had to leave their homes due to hurricanes, floods or other natural disasters. As the Census Bureau stated in a 2018 Federal Register notice announcing the residence rules for the 2020 census: “The proposed residence guidance already allows people who are temporarily displaced by natural disasters to be counted at their usual residence to which they intend to return.”

But for those who are unsure whether they will return, the bureau’s residence rules state: “People who do not have a usual residence, or who cannot determine a usual residence, are counted where they are on Census Day.”

Counting yourself without a unique census code

The 2020 census began with a door-to-door count in remote Alaska in late January. Census mailings went to most U.S. households beginning March 12, inviting them to respond online, by mail or by telephone, using a unique census code. Those who have not responded are supposed to receive a paper questionnaire in the mail this month.

Because of COVID-19, the bureau says it will be collecting census responses until Oct. 31, three months later than originally planned, but the agency prefers that people answer as soon as possible. On Aug. 11, the agency is scheduled to begin knocking on doors of households that did not respond, according to the latest Census Bureau guidance.

The Census Bureau also asked Congress to extend its Dec. 31 legal deadline by four months to deliver apportionment counts dividing up seats in the U.S. House of Representatives among the states. The bureau also asked for a four-month extension of its April 1, 2021, deadline to release detailed state-by-state data for redistricting purposes.

College students living in college-owned housing are supposed to be counted by their institutions, with the information sent directly to the Census Bureau. College students in private housing are supposed to respond on their own.

People can be counted where they are living even if they do not have the unique census identification number that came with Census Bureau mailings at their original address. The bureau also says that people can correct their original census responses. Census officials say they will weed out any duplicate responses.