When Did Competitive Sports Take Over American Childhood?

It all started in 1852, when Massachusetts became the first state to require kids to go to school.

American children not only participate in myriad afterschool activities, they also compete. In 2013 7.7 million children played on a high-school sports team, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations. At the same time U.S. Youth Soccer, the national organization that oversees travel soccer, registers more than three million children between the ages of five and 19 who play at a competitive level (not taking into account the thousands of young children who play recreationally each year). Middle-class kids routinely try out for pay-to-play all-star teams, travel to regional and national tournaments, and clear off bookshelves to hold all of the trophies they have won.

It has not always been this way. About a hundred years ago, it would have been lower-class children competing under non-parental adult supervision while their upper-class counterparts participated in noncompetitive activities like dancing and music lessons, often in their homes. Children’s tournaments, especially athletic ones, came first to poor children—often immigrants—living in big cities.

Not until after World War II did these competitive endeavors begin to be dominated by children from the middle and upper-middle classes. The forces that have led to increasing inequality in education, the workplace, and other spheres have come to the world of play.

How did this transformation happen? Things first began to change in the 19th century, with the start of the mandatory-schooling movement. Massachusetts made schooling compulsory in 1852, though it wasn’t until 1917 that the final state, Mississippi, passed a similar law. With the institution of mandatory schooling, children experienced a profound shift in the structure of their daily lives, especially in the social organization of their time. Compulsory education brought leisure time into focus; since “school time” was delineated as obligatory, “free time” could now be identified as well.

What to do with this free time? The question was on the minds of parents, social workers, and “experts” who doled out advice on child-rearing. The answer lay partly in competitive sports leagues, which started to evolve to hold the interest of children. Urban reformers were particularly preoccupied with poor immigrant boys who, because of overcrowding in tenements, were often on the streets. Initial efforts focused on the establishment of parks and playgrounds, and powerful, organized playground movements developed in New York City and Boston. But because adults didn’t trust boys to play unsupervised, attention soon shifted to organized sports.

Sports were seen as important in teaching the “American” values of cooperation, hard work, and respect for authority. According to historian Robert Halpern, progressive reformers thought athletic activities could prepare children for the “new industrial society that was emerging,” which would require them to be physical laborers. Organized youth groups took on the responsibility of providing children with sports activities.

In 1903 New York City’s Public School Athletic League for Boys was established, and formal contests between children, organized by adults, emerged as a way to keep the boys coming back to activities, clubs, and school. Formal competition ensured the boys’ continued participation since they wanted to defend their team’s record and honor. The Elementary Games Committee of the PSAL organized interschool athletic competition for boys through track and field meets and basketball and baseball contests; in 1914 2040 boys vied for the city championships in track and field held at Madison Square Gardens.

By 1910 17 other cities across the United States had formed their own competitive athletic leagues modeled after New York City’s PSAL. Settlement houses and ethnic clubs soon followed suit. The number of these boys’ clubs grew rapidly through the 1920s, working in parallel with school leagues.

But during the Depression many clubs with competitive leagues suffered financially and had to close, so poorer children from urban areas began to lose opportunities for competitive athletic contests organized by adults. Fee-based groups, such as the YMCA, began to fill the void, but usually only middle-class kids could afford to participate. At roughly the same historical moment athletic organizations were founded that would soon formally institute national competitive tournaments for young kids, for a price. For example, national pay-to-play organizations, such as Pop Warner Football came into being in 1929.

At the same time, many physical-education professionals stopped supporting athletic competition for young children because of worries that leagues supported competition only for the best athletes, leaving the others behind. Concerns about focusing on only the most talented athletes developed into questions about the harmfulness of competition. In the end this meant that much of the organized youth competition left the school system, even to this day, for elementary-school kids (though this isn’t true for high-school sports, as detailed in The Atlantic’s most recent cover story, “The Case Against High-School Sports”).

But it did not leave American childhood.

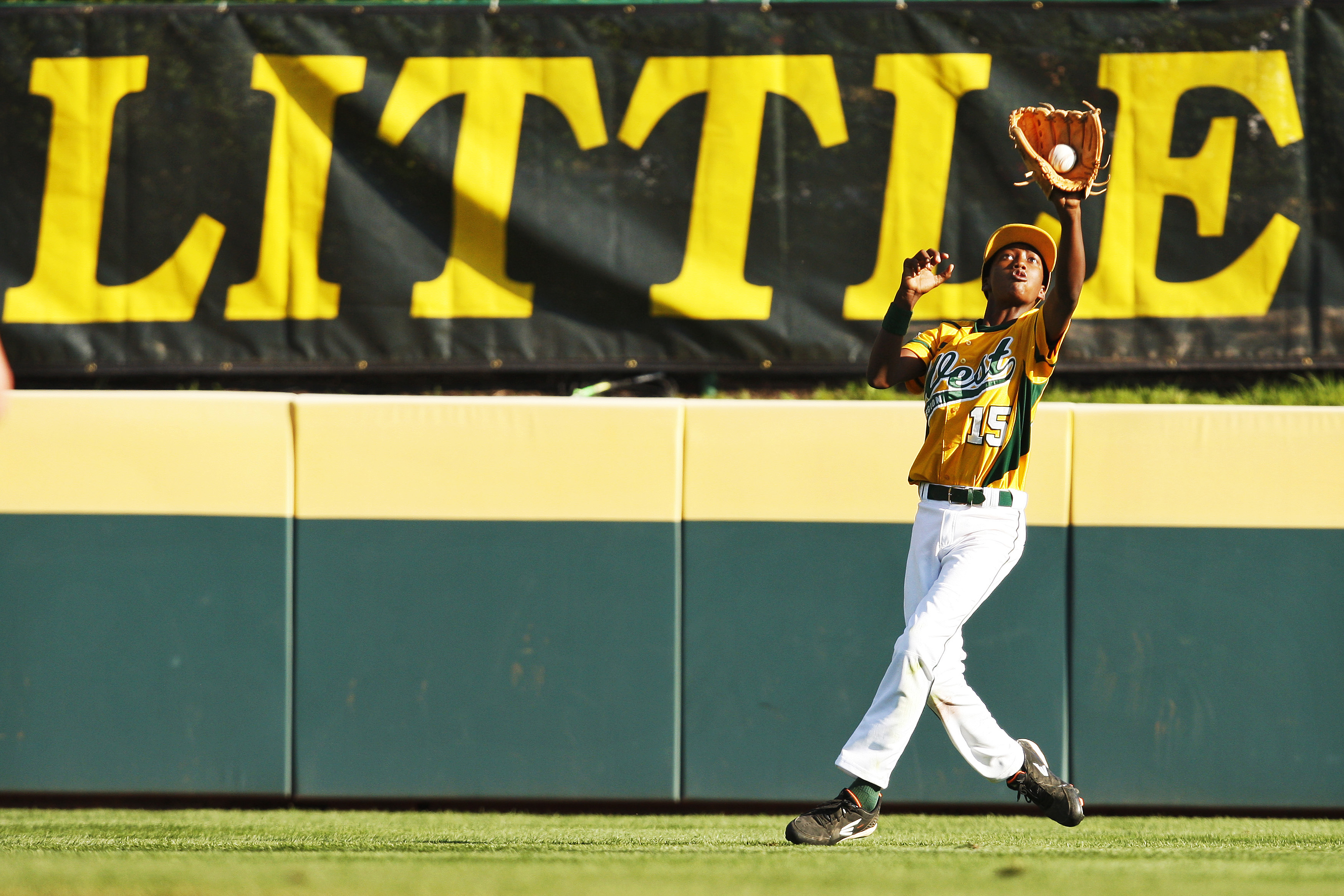

One of the first children’s activities to become nationally organized in a competitive way, and certainly one of the most well-known and successful youth sports programs, is Little League Baseball. After its creation in 1939 the League held its first World Series only a decade later, in 1949. In the ensuing years Little League experienced a big expansion in the number of participants—just a decade later, in 1959, Little League sponsored 5000 leagues each with multiple team rosters organizing 15-20 young boys. As this model of children’s membership in a national league organization developed, fees to play and compete only increased.

With the success of these fee-based national programs it became more difficult to sustain free programs. Most elementary schools no longer sponsored their own leagues due to concerns over the effects of competition on children, similar to concerns voiced in the 1930s. The desire to dampen overt competition in school classrooms was part of the self-esteem movement that started in the 1960s.

The self-esteem movement focused on building up children’s confidence and talents without being negative or comparing them to others. As the movement did not reach outside activities, such as sports, private organizations rushed to fill the void. Parents increasingly wanted more competitive opportunities for their children and were willing to pay for it.

By the 1960s parents and kids spent time together at practices for sports that were part of a national structure: Biddy basketball, Pee Wee hockey, and Pop Warner football. Even non-team sports were growing and developing their own formal, national-level organizations run by adults. For example, Double Dutch jump-roping started on playgrounds in the 1930s; in 1975 the American Double Dutch League was formed to set formal rules and sponsor competitions.

Historian Peter Stearns writes that the 1960s saw, “a growing competitive frenzy over college admissions as a badge of parental fulfillment.” Parental anxiety reached a new level because the surge in attendance by Boomers had strained college facilities, and it became increasingly clear that the top schools could not keep up with the demand, meaning that students might not be admitted to the level of college they expected, given their class background. This became even more problematic with the rise of coeducation and the nationalization and democratization of the applicant pool, fueled by the GI Bill, recruiting, and technology that produced better information for applicants. In The Game of Life: College Sports and Educational Values, former Princeton University president William Bowen (along with administrator James Shulman) link this parental anxiety to an increased focus on athletics as a protection for kids against getting pushed out of colleges where they “deserved” to earn slots.

Interestingly, the competitive frenzy over college admissions did not abate in the 1970s and 1980s, when it was actually easier to gain admission to college, given the decline in application numbers after the Baby Boomers. Instead, more aware of the stakes, families became more competitive and even more competitive afterschool activities for kids continued to develop, evolve, and intensify, particularly in the 1990s. For example, in 1995 the Amateur Athletic Union sponsored about 100 national championships for youth athletes; about a decade later that number had grown to over 250.

I find, along with economists Valerie and Garey Ramey in their work “The Rug Rat Race,” that with the Echo Boom in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it once again became harder to get into a “top” college. It was not just that there was an increase in the college-age population, but also that there were record numbers of applications to the most elite colleges and universities with students applying to many more schools than ever before.

This reality has created an incredibly competitive atmosphere for families now, as parents start earlier and earlier in their children’s lives on the long march to college admission. In some parts of the country some parents with higher class standing start grooming their children for competitive preschool admissions, setting their children on an Ivy League track from early on.

Competitive children’s activities have certainly evolved since they began in late 19th-century America. Now there are more activities, a greater number of competitions, and a change in the class backgrounds of competitors. It’s thanks to changes in the 20th-century educational system—like compulsory schooling, the self-esteem movement, and higher-stakes college admissions—that this is how American families are spending leisure time today.