Wu Jinglian and His Disciples Were The Key Brains Behind Reform

Editor’s note:

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the launch of China’s reform and opening-up policy that has transformed the nation into an economic powerhouse. As the world seeks to better understand the major reforms underpinning the country’s rapid economic expansion, Chinese economists are a key group worth watching due to their role advising the country’s top leadership and increasing public understanding of the market economy. By doing so, they helped reshape what was once one of Asia’s most backward economies.

The historic turning point came in December 1978, when the ruling Communist Party called for “liberating thought,” marking the beginning of the reform period.

Caixin has detailed the careers of some of China’s most influential economists from the reform era. The five-part series examines their academic achievements as well as their impact on China’s economic reforms to present readers with a clearer picture of what shaped the world’s second-largest economy.

The following is the second installment in a five-part series about the economists behind China’s reform.

Wu Jinglian was one of the most influential economists over the past four decades as China steered away from Soviet-style planning to a more market-oriented system that has propelled its economy to become the world’s second-largest.

A firm believer in market-oriented economics, Wu became a go-to man during the reform era for top Chinese leaders, who frequently adopted his proposals and turned them into national policy.

He and his disciples, many of whom would go on to their own high positions, are known as proponents of “coordinated reforms,” where changes are made in a coordinated way to manage everything from taxes to trade, banks and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), as well as monetary and foreign exchange policies.

“Wu maintained the biggest and the longest influence over China’s economic reform among all economists,” Xu Chenggang, a professor of economics at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, told Caixin.

A new faith

Born in 1930, Wu fervently supported revolution as a teenager, and would secretly listen to radio broadcasts from Yan’an, then the headquarters of the Communist Party. He transcribed a 1947 speech by Mao Zedong on the party’s political, economic and military agenda to spread among his friends.

He remained true through his 20s to the political movement that called for people to “remold their thinking” and accept Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong thought. He once demanded that his mother, a lawyer and successful newspaper manager who supported the party during the Chinese civil war, not sit on a couch because it was “not proletarian.” He even proclaimed that “each man should own no more than two shirts,” according to a biography authored by financial writer Wu Xiaobo. Even after his early career at an elite government think tank exposed him to Soviet theories’ deficiencies for guiding economic activity on the ground, he continued believing in the centrally planned economic model.

But then he witnessed the Chinese economy go to the brink of collapse during the chaotic Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976. Thrown into a “reeducation camp,” Wu made close friends with prominent liberal economist Gu Zhun, who was also being persecuted. Wu became increasingly suspicious of the philosophies behind his earlier training and began a conversion to liberalism and belief in market economics.

China’s opening up in the 1980s allowed Wu to engage more with foreign academics, who told him about their experiences and the lessons of economic reform from other communist states. In that environment, Wu could also conduct in-depth studies into Western economic theories and methodologies.

In January 1983 he went to Yale University, where he spent a year and half as a visiting scholar at its Department of Economics and Institution of Social and Policy Studies. Apart from his research, Wu “participated in the seminars of the postgraduates and sat in on the undergraduates’ courses, assiduously making up for studies in micro and macroeconomics which he had missed,” according to a biography written by Liu Hong, one of his former assistants.

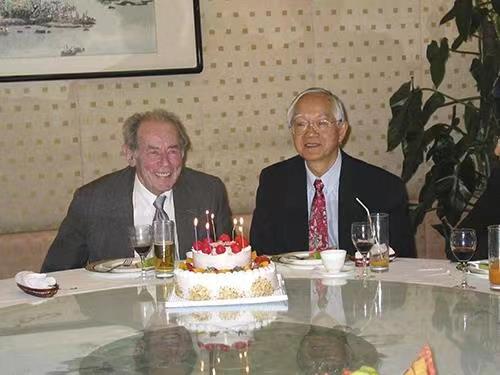

|

Wu Jinglian and Janos Kornai celebrate their birthdays in Beijing |

During that time Wu better acquainted himself with Janos Kornai, a Hungarian economist teaching at Harvard University whom he had previously met at an international conference. Kornai, who enormously inspired Wu over the following decades, had a profound impact on China: his books became textbooks for economics students, and his works provided a theoretical basis for the Chinese government to eventually renounce the command economy.

Kornai coined the term “soft budget constraint” in the late 1970s to characterize the practice of the government and state-owned banks continuing to fund insolvent companies to keep them from being shut down, generating enormous bad debt.

That theory strengthened a case for the government’s drastic overhaul of SOEs in the 1990s, including massive shutdowns and layoffs. Some of the largest were publicly listed, with the aim of establishing modern corporate governance to improve efficiency. That theory remains relevant to China’s ongoing efforts to reform SOEs.

Wu was instrumental in helping turn Kornai’s ideas into practice in China in order to reform the economy, according to Xu of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.

“It was impossible for Professor Kornai, as a foreigner, to have a direct impact on China,” said Xu, who studied under the Hungarian at Harvard. “But his theories played a significant role in China’s reform in the 1980s and 1990s. That was due to the promotion by some Chinese, and the most important among those people was Wu Jinglian.”

“Wu was very open-minded and good at assimilating foreign ideas. Many of his proposals that drove policymaking originated from abroad,” he said.

Brains of Beijing

In April 1986, Wu was appointed a deputy director of the Economic System Reform Program Design Office of the State Council, a temporary body directly under the cabinet tasked with drafting major reform policies for the next two years. At the office, he led a team of researchers considering the first framework for coordinated reforms, which was supported and highly rated by then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, Wu said in a 2005 article.

Economists from that team would later be called members of the “coordinated reformist school,” in contrast with scholars who wanted SOE reforms to be done first and foremost.

Many of those researchers were eventually promoted to top positions at key economic and financial departments, including Zhou Xiaochuan, the longest-serving governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC); Lou Jiwei, an ex-finance minister; and Guo Shuqing, chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission and the PBOC’s current party chief.

Among them was former vice chair of the National People's Congress Financial and Economic Affairs Committee Wu Xiaoling, who was named one of the most influential women of the early 2000s by Forbes and the Wall Street Journal. She participated in a 1992-1994 program directed by Wu Jinglian; in a few years’ time she was promoted to be the first ever female administrator of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE). In this capacity, she helped China weather the Asian financial crisis that broke out in 1997. Wu Xiaoling was also behind the introduction of private equity funds to China in 2007.

In early 1992, Deng, then retired but still powerful, settled a heated national debate over whether market reform was a capitalist movement with speeches during his famous tour to southern China in support of the reformers. In April of that year, Wu proposed party leaders make the establishment of a socialist market economy the goal of reforms. This change was officially adopted at the 14th Party Congress held six months later.

Coordinated reformist school

The researchers who worked with Wu at the State Council body in 1986 gathered again for the 1992-1994 project he led. That project looked for answers on how China’s market reform should proceed in general, and what specific measures should be taken in different sectors.

They offered advice on a comprehensive range of issues, including strengthening the central bank’s role in adjusting the money supply and supervising commercial lenders, a roadmap for full convertibility of the yuan, transformation of other levies into a value-added tax and the introduction of a payroll tax.

Other topics included the overhaul of central-local fiscal dynamics, corporatization of SOEs, and the building of a housing market and a social security system.

Many suggestions were included in an official document endorsed by the party at a plenum in November 1993.

Wu and his other colleagues’ recommendations, such as withdrawing state capital from non-strategic sectors, continued to be accepted by the party in following years.

More recently, Wu, now 88 and an honorary professor at the China Europe International Business School, has advocated a market economy governed by the rule of law to fight corruption.

Wu, who is also a researcher at the State Council’s think tank Development and Research Center, attributed his success in influencing Chinese policy mostly to luck, suggesting he was embraced by political leaders keen on change in an era of reform.

“Among all the economists (in China), I may be the one who made the least mistakes. But the decisions (to advance reform) were made by politicians, not economists,” he was quoted as saying in his daughter, Wu Xiaolian’s 2007 book “My Father Wu Jinglian and I.”

Contact reporter Fran Wang (fangwang@caixin.com)

- 1Chinese Cement Maker Halts Trading After Shares Fall 99% in 15 Minutes

- 2Update: China’s First-Quarter GDP Growth Beats Expectations at 5.3%

- 3Cover Story: Alibaba Renews Strategy Reset to Revive Growth Momentum

- 4Weekend Long Read: How China Can Avoid the Worst Path to Reviving Consumer Spending

- 5In Depth: Fusion Sector Heats Up as China Pursues Next-Gen Nuclear Power

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas