The Problem With #BelieveSurvivors

It’s important to listen to those who come forward—and also to those accused.

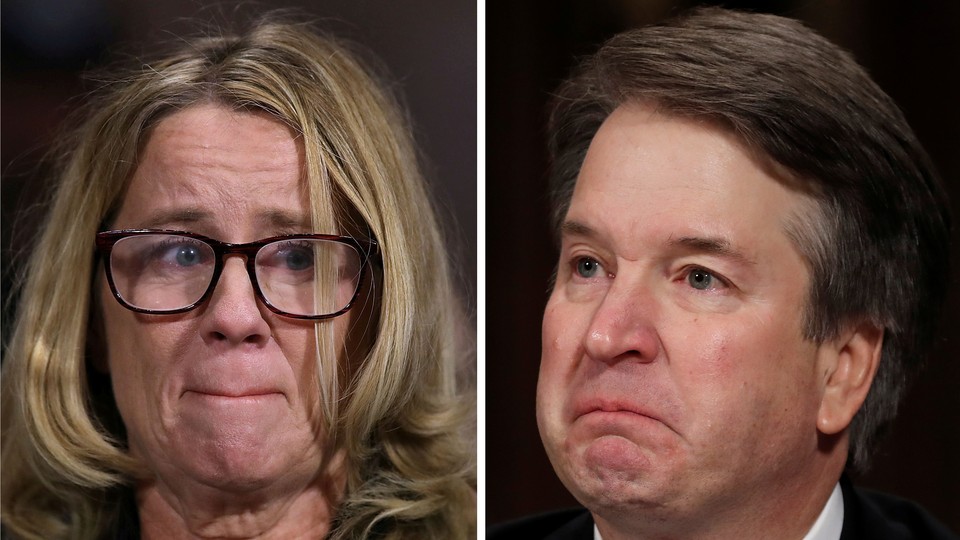

We are now in a time of chronic national convulsions, and the latest, over the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court, has resulted in the wrenching public and private testimony of women who have been sexually assaulted and who have never before spoken about it. Of course, this outpouring has a hashtag: #BelieveSurvivors. Women who tell their stories should have the support, and belief, of loved ones, friends, and a therapeutic community.

But when a woman, in telling her story, makes an allegation against a specific man, a different set of obligations kick in.

Even as we must treat accusers with seriousness and dignity, we must hear out the accused fairly and respectfully, and recognize the potential lifetime consequences that such an allegation can bring. If believing the woman is the beginning and the end of a search for the truth, then we have left the realm of justice for religion.

Whether an investigation takes place at a school, at a workplace, or in the criminal-justice system, neutral fact-finding must apply, regardless of how disturbing we find the offense, the group identity of the accused, or the political leanings of those involved. History demonstrates that ascribing honesty or dishonesty, criminality or righteousness solely on the basis of gender or race doesn’t increase the amount of equity in the world.

The best reporting of the #MeToo movement has shown that when journalists examine all the possible holes in an accuser’s account, find corroborating witnesses and documentary evidence, and give the accused the opportunity to respond, they make the victim’s story more powerful. (Men can sexually assault men, women can sexually assault women, and women can sexually assault men. But the vast majority of these allegations are of males assaulting females.)

Unfortunately, we must also accept the reality that the fact-finding process will, by its very nature, cause pain to both parties. The New York Times editorial page on Monday blasted how Christine Blasey Ford has been treated since she went public with her account of a frightening sexual attack by a then-teenage Brett Kavanaugh. It noted that the 11 Republican men on the Judiciary Committee brought in a female prosecutor to “chip away” at Ford’s testimony.

Certainly, the hearing was odd, flawed, and ripe for parody on Saturday Night Live. But the Republican questioning of Ford was not particularly harsh, and while it was intended to knock her credibility, that’s the purpose of adversarial proceedings. In the end, Ford’s answers and her demeanor buttressed her account, whereas Kavanaugh’s histrionics led some to question his fitness for the bench.

I am one of the many women who experienced sexual assaults earlier in life and never told anyone, until I wrote a story about these events for Slate in 2012. It was at the time of the Jerry Sandusky trial, and many victims were questioned about why they had kept quiet. So I explained why I didn’t tell. Like Ford, I have a vivid and visceral recollection of the assaults and a missing memory of the peripheral details, especially what happened afterward.

In one instance, when I was 15, I was visiting my best friend, and her father drove me home after dinner. He parked in front of my house and started babbling about how a man gets angry and frustrated when a wife won’t meet his needs. Then he lunged at me, putting his hands on my breasts and his mouth on mine. I pushed him off, escaped from the car, and got to my front door. But the rest of the night, what happened after I entered my home and pretended everything was fine, is a blank.

I have also spent the past several years reporting on the injustices done to accused students—almost all men—in campus sexual-assault proceedings under Title IX, the federal law that forbids sex discrimination in schools. (Here is my Atlantic series on the subject.) During the Obama administration, that law became the basis for vast college bureaucracies that govern the sexual behavior of students.

On campuses, many Title IX allegations spring from sexual encounters (often lubricated by alcohol) between young adults that both parties agree began consensually. Frequently, an allegation turns on whether the accused failed to follow the campus rules of “affirmative consent,” which essentially requires that unambiguous consent, preferably verbal, be obtained for each touch, each time, even between established partners.

In many ways, the Ford accusation differs from the typical Title IX case. Both Ford and Kavanaugh were minors—she says she was 15 years old—and both parties agree there was no consensual sexual contact. She describes a sudden attack at a party; he denies even being at the party or ever doing anything to her. But the Senate Judiciary hearings echoed the quasi-trials that regularly take place on college campuses. Patricia Hamill, a Philadelphia-based attorney who represents students in Title IX cases, told me the hearing was very recognizable to her. “No witnesses to what happened,” she said. “No way to corroborate other than looking at the emotional tenor of how they answered the questions.”

I have interviewed many accused students who say the allegations against them were grossly unfair, and I have written about cases in which the record supports their assertions. I have yet to talk to an accused student, even one who was eventually cleared, whose life wasn’t profoundly damaged; every one has told me that at some point he considered suicide. So I understand that Kavanaugh’s anguish was real, and I believe he was entitled to express it. What’s worrisome is that he was unable to move beyond a puerile and partisan outburst. (Incidentally, it’s extremely unlikely that a college student would be found “not responsible” for a campus sexual-misconduct allegation had he behaved the way Kavanaugh did.)

In one sense, the hearing was theater, not fact-finding, because except for a handful of undecided senators, the rest had already made up their mind about the accusation based entirely on their desire to either seat or thwart Kavanaugh. Republicans sought to discredit Ford and quash the airing of her story. President Donald Trump, in a speech Tuesday night in Mississippi, openly mocked her.

As for the Democrats, in a Senate floor speech the day before the hearing, Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York announced that it was unnecessary for her to hear Kavanaugh’s testimony. Gillibrand declared, “I believe Dr. Blasey Ford.” Many Democrats, in keeping with #BelieveSurvivors, are taking their certainty about Ford’s account and extrapolating it to all accounts of all accusers. This tendency has campus echoes, too: The Obama administration’s well-intended activism on campus sexual assault resulted in reforms that went too far and failed to protect the rights of the accused.

The impulse to arrive at a predetermined conclusion is familiar to Samantha Harris, a vice president at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE). Harris says that under Title IX, students who report that they are victims of sexual misconduct must be provided with staffers who advocate on their behalf. These staffers should “hear them out, believe them, and help them navigate the process,” she said, but added, “When the instruction to ‘believe them’ extends to the people who are actually adjudicating guilt or innocence, fundamental fairness is compromised.” Harris says that many Title IX proceedings have this serious flaw. As a result, in recent years, many accused students have filed lawsuits claiming that they were subjected to grossly unjust proceedings; these suits have met with increasingly favorable results in the courts.

Hamill also described to me the undermining effects of unreliable procedures. “There is not a feeling of fundamental fairness in college settings a lot of the time,” she said, “and so then the results often feel illegitimate or not credible.” She added that she welcomed the voices of women in society at large telling their stories, but urged that we should not repeat the mistakes made under Title IX. “You have to have integrity to a process that allows people to bring their claims forward but also allows for the accused to meaningfully defend themselves.”

This should have been the lesson that emerged from the resignation from the U.S. Senate of the Democrat Al Franken of Minnesota. Last year, Franken was publicly accused by several women of grabbing them while being photographed together. He welcomed the Senate Ethics Committee inquiry that was underway, saying he was confident it would clear him. But last December, after another woman came forward, Gillibrand became the first senator to announce that Franken should quit immediately, declaring that she believed the women. Other Democratic senators quickly joined the call, and Franken soon resigned. His departure, though, has continued to leave many Democrats uneasy about both its abruptness and the unresolved questions about the allegations.

We don’t even have to imagine the dangers of a system based on automatic belief—Britain recently experienced a national scandal over such policies. After widespread adoption of a rule that law enforcement must believe reports of sexual violation, police failed to properly investigate claims and ignored exculpatory evidence. Dozens of prosecutions collapsed as a result, and the head of an organization of people abused in childhood urged that the police return to a neutral stance. Biased investigations and prosecutions, he said, create miscarriages of justice that undermine the credibility of all accusers.

The legitimacy and credibility of our institutions are rapidly eroding. It is a difficult and brave thing for victims of sexual violence to step forward and exercise their rights to seek justice. When they do, we should make sure our system honors justice’s most basic principles.