Al Franken, That Photo, and Trusting the Women

From Eve to Aristotle to Sarah Huckabee Sanders, a brief history of looking at half the population and assuming the worst

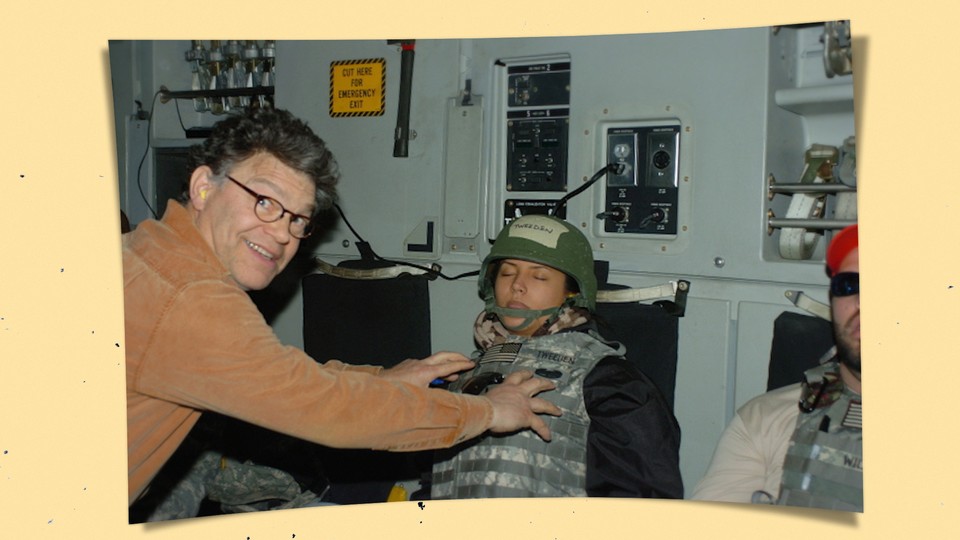

The picture was striking. The military airplane. The sleeping woman. The outstretched hands. The mischievous smile. The Look what I’m getting away with impishness directed at the camera.

On Thursday, Leeann Tweeden, a radio host and former model, came forward with the accusation that Senator Al Franken of Minnesota had kissed her against her will during a 2006 United Service Organizations trip to Kuwait, Iraq, and Afghanistan. In a story posted to the website of Los Angeles’s KABC station, Tweeden shared her experience with Franken. She also shared that photo. “I couldn’t believe it,” she wrote. “He groped me, without my consent, while I was asleep.”

I felt violated all over again. Embarrassed. Belittled. Humiliated.

How dare anyone grab my breasts like this and think it’s funny?

I told my husband everything that happened and showed him the picture.

I wanted to shout my story to the world with a megaphone to anyone who would listen, but even as angry as I was, I was worried about the potential backlash and damage going public might have on my career as a broadcaster.

But that was then, this is now. I’m no longer afraid.

I’m no longer afraid. It’s a sentiment that has been steadily spreading, in recent weeks, among those who have been sexually harassed and preyed upon—not among all of them, certainly, but among many more than before. Tweeden, however, had another reason not to fear coming forward: She had, unlike so many other victims of harassment, hard evidence. This was not a case of her word against his, he said against she said; Tweeden had, via that photo of Franken groping and grinning, the receipts. Because of that, members of the public had no other choice but to do the thing that so many people, for so long, have been extremely hesitant to do: Take her at her word. Trust the woman and the story she tells.

It remains to be seen whether the #MeToo moment—the “Weinstein Moment,” it is also called, in ironic commemoration of the man whose alleged actions led to the flinging open of the floodgates—will prove to be a pivotal one in the sweeping context of American cultural history. There have been, after all, other such moments. There have been other such movements. But one of the most significant elements of #MeToo as a phenomenon is the fact that it has served, effectively, as its own kind of photograph, its own kind of receipt. There are so many women, telling such similar stories. They are painting a picture. They are daring you to look. “Pics or it didn’t happen,” as they say; well, here’s the pic. That makes the #MeToo moment not only about justice—and about women being required, once again, to insist on their own humanity—but also about something both simpler and more fraught: belief itself. Will this be the moment that we—we as a culture, we as a collective—finally start taking women at their word?

The Franken revelation came, as it happened, after a week of discussion about Roy Moore, the U.S. senatorial candidate from Alabama, after multiple women came forward to say that he had preyed upon them as teenagers. They did not—save for a yearbook signature that Moore’s defenders have suggested could be fraudulent—have photographic evidence. And of course they didn’t: Harassment and assault, by their nature, often take place in the shadows, away from others, in intimate places that are hidden and walled and secret. This, in turn, is in many cases used as a weapon against the victims. And so, soon after Leigh Corfman came forward to share her alleged experience with Moore, when she was a girl of 14—the clock ticks predictably—a rumor that was entirely unfounded began spreading: The Washington Post, it went, had paid the women to speak on the record. Divorces were mentioned; financial troubles rehashed; characters impugned. Tick, tick, tick.

Corfman and Tweeden are only two of so many women, and their experiences differ greatly—and yet, what they underwent while coming forward to share their stories makes for an instructive comparison. Tweeden, with her photo evidence, was believed because it was unreasonable not to believe her. Moore’s accusers were believed in some quarters, but in many others were met with doubt: If true, if true, if true. (“If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you / But make allowance for their doubting too …”) Partisan politics are at play in all that, certainly, but so too are politics of a much more ancient strain: Doubting women, after all, is an age-old game. #MeToo and its celebration of women’s agency is fighting centuries’ worth of ingrained beliefs about women’s propensity to deceive, to manipulate, to doctor the picture.

Aristotle—he of the “women are mutilated men” conviction—believed enthusiastically that women’s inferior bodies accounted for their inferior minds, and that this led, in turn, to a capacity for deception. (“Wherefore women are more compassionate and more readily made to weep,” he declared, they are also “more jealous and querulous” than men. “The female,” he continued, “also is more subject to depression of spirits and despair than the male. She is also more shameless and false … than the male.”) The Greek physician-philosopher Galen of Pergamon refined that idea in his Complexion theory—complexion in this case having less to do with the skin and more to do with the balance of the “humors”: the hot, the cold, the dry, and the wet, as anatomical approximations of earth, wind, fire, and water. Women were colder and wetter than men, he believed; this anatomical reality made them more apt to manipulate and deceive. As one summary of the matter put it: “Aristotle and Hellenistic medicine attributed woman’s fickle attitudes, immorality, and insatiable sensory appetite to biology—excessive moisture. She’s too soggy.”

The ideas trickled down, as so many ancient assumptions did, through the centuries. (“I have heard of your paintings too, well enough,” Hamlet glowers to Ophelia, and really to all women. “God has given you one face and you make yourselves another.”) Eve tempted; Delilah betrayed; Jezebel deceived; Cassandra told truths that were assumed to be lies. Calypso beguiled Odysseus—himself a master manipulator—into her island cavern not with her home-decorating skills, but with that standby of gendered scapegoatery: feminine wiles. Men and women, the ancients assumed through their literature, are at odds with one another; women, generally lacking economic or political power, exert themselves through manipulations. Lysistrata is a comedy; it is also, in that sense, an insight.

Men lie, too, of course. Yet, in general, their lies have been treated as exceptions while women’s have been treated as a rule. Notions of honor as a function of truth-telling—“Honest Abe,” Washington’s cherry tree—have been construed over time as specifically male aspirations. (The words testimony and testify, one theory goes, are rooted in the fact that the men of ancient Rome, as a gesture of trustworthiness and truth-telling, cupped their testicles.) Women, on the other hand, the mythologies have gone, use their bodies to manipulate and cajole and entrance: Calypso’s “cavern” is a place that is also a not terribly subtle metaphor. As the author Dallas G. Denery II put it in 2015’s The Devil Wins: A History of Lying From the Garden of Eden to the Enlightenment: “Over 1,200 years of endlessly repeated authority transmitted in the form of religious doctrine, natural philosophy, and stories, poems and plays, jokes and anecdotes” framed women as men’s natural adversaries. And women have done their fighting, the long-running story has insisted, though seductions of both body and psyche: “sweet words, fallacious arguments, tears, and exposed breasts.”

It’s an ancient idea that has extended to the modern-day United States (as, of course, to many other places). Notions of “hysteria.” Dismissals of women’s anger as at once irrational and manipulative. Fear of—and interest in—witches and their crafts: “And I’ve got no defense for it / The heat is too intense for it / What good would common sense for it do?” And it has lived on, in even more recent times, in the protestations of GamerGate, and the plot of Gone Girl, and the title of Pretty Little Liars, and the trope of the gold digger, and the notion of the femme fatale, and the paradigm of “the Madonna and the whore,” and the racist logic of the “welfare queen.” It’s in every lyric of “Blurred Lines”—and every “but look how she dresses” rebuttal, and every “if true” dismissal. As Soraya Chemaly, writing for HuffPost in 2014, put it: “If she expresses herself in a combative way in response to a hectoring lawyer or reporter, she is going to be disliked. If she is silent, she will be distrusted. If she talks too much, she is thought to be making stories up. If she is a woman of color, well, all of that on steroids plus some.”

And around it goes. In 2003, a woman set off an airport metal detector en route to a vacation she was taking without her husband: He had forced her to wear a chastity belt forged of metal, she explained to the confused security agents, to ensure that she would be faithful in his absence. In 2017, a (male) developer released an app that promises to reveal what a given woman looks like without makeup—Hamlet’s anger at being deceived by women who paint their faces, finally getting its champion. The same year, a Dutch production company announced the creation of a new reality show—Raped or Not, it’s teasingly titled—in which guest panelists will make that determination on behalf of the pair in question. Until very recently, U.S. law enforcement had “corroboration requirements” for allegations of rape. One of the investigators working for the Philadelphia Police Department’s sex-crimes unit nicknamed his workplace “the lying bitches unit.”

These things are not unrelated. They are, on the contrary, bound together in the most intimate of ways. If true. If true. If true. In one way, certainly, it’s a fitting refrain for the America of 2017, with all its concessions to the conditional tense: alternative facts, siloed reality, a political moment that has summoned and witnessed a resurgence of the paranoid style. And yet it’s also an abdication—“moral cowardice,” the journalist Jamelle Bouie put it—and in that sense is part of a much longer story. If true is a reply, but it has in recent cases become more effectively a verb—a phrase of action, done to women, to remind them that they are doubted. If true used as a weapon. If true used as a mechanism to enforce the status quo. For years. For centuries. The woman says, “This happened.” The world says, “If true.”

No wonder so many women, for so long, have preferred silence. No wonder they have found it more tolerable to bear their experiences on their own—to keep them safely locked away, monstrous but contained—than to share them and risk the inevitable results. The economics of truth-telling have been too stark, too brute. They could speak; very likely, however, people would listen but not hear. Very likely, they would reply with excuses and questionings and punishments and shame: You probably misunderstood. Anyway, that’s just how he is. And don’t take this the wrong way, but that was a pretty short skirt to be wearing to work. And how do we know for sure that you’re not making it all up?

In recent weeks, as similar conversations have emerged about Bill Clinton, the fact that more than 16 women have accused President Trump of sexual misconduct—a story that has lurked in the shadows of his campaign and his presidency—has reemerged in American media. “Donald Trump’s Sexual Assault Accusers Demand Justice in the #MeToo Era,” one headline—in People—summed it up. The accusers, however, just as the #MeToo movement itself, are battling a powerful foe. Last month, during a press conference, a reporter asked Sarah Huckabee Sanders about those women and their stories. Her reply did not include an “if true.” Instead, the White House press secretary declared, on behalf of the American president: The women, all of them, were lying.